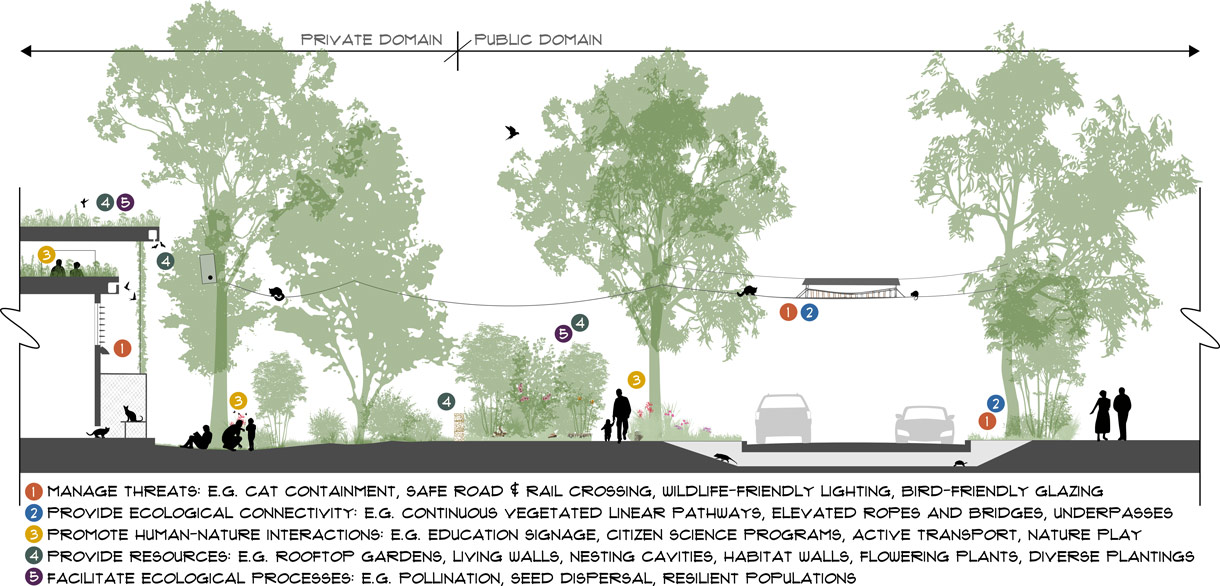

Improving urban design to bring nature back into our cities

Nature friendly urban design is being encouraged to make our cities more liveable.

Measuring digital inclusion to increase equitable access for all

A long-term research project and index is providing vital information about digital inclusion to improve access to and effective use of digital technologies for all Australians.

Developing inclusive health programs and digital literacy in Southeast Asia

Research at RMIT Vietnam is helping to improve access to health services and boost digital literacy for people living with a disability in Vietnam and Indonesia.

Enhancing Community Resilience in Honiara, Solomon Islands

Creating real-world impact on climate resilience by building local capacity and enhancing agency.