Australia's first nano-biosensing facility was established after a grant of $500,000 was given by the Ian Potter Foundation.

The 50th Anniversary Commemorative Grant has helped to create a new $1.2m research facility.

Co-funded by RMIT, the facility will support the development of cheap, ultra-precise and easy-to-use nano-devices for the diagnosis and detection of health hazards.

The new facility will lead research projects on nano-devices that can cut the diagnosis time of meningococcal from hours to minutes, as well as producing inexpensive nano-tools for diagnosing malaria in developing countries, that can give almost instant results and requires no medical training to use.

The Ian Potter NanoBiosensing Facility will bring together bio-containment infrastructure and nano-biosensensing laboratories for the first time, allowing researchers to work with pathogens and microorganisms within a nanotechnology precinct.

Artificial enzymes use visible light to break down and kill bacteria

Artificial enzymes use visible light to break down and kill bacteria

According to the director of the new facility, Associate Professor Vipul Bansal:

The point-of-care nano-devices we’re developing are not only inexpensive and simple to use, but also extremely sensitive, so they give an accurate diagnosis almost instantly.

The facility is destined to become a NanoBioSensing Hub in Australia.

Importantly, it will also help us advance our research through the establishment of international collaborations that can maximise the global impact of these life-saving, leading-edge technologies.

‘NanoZymes’ use light to kill harmful bacteria

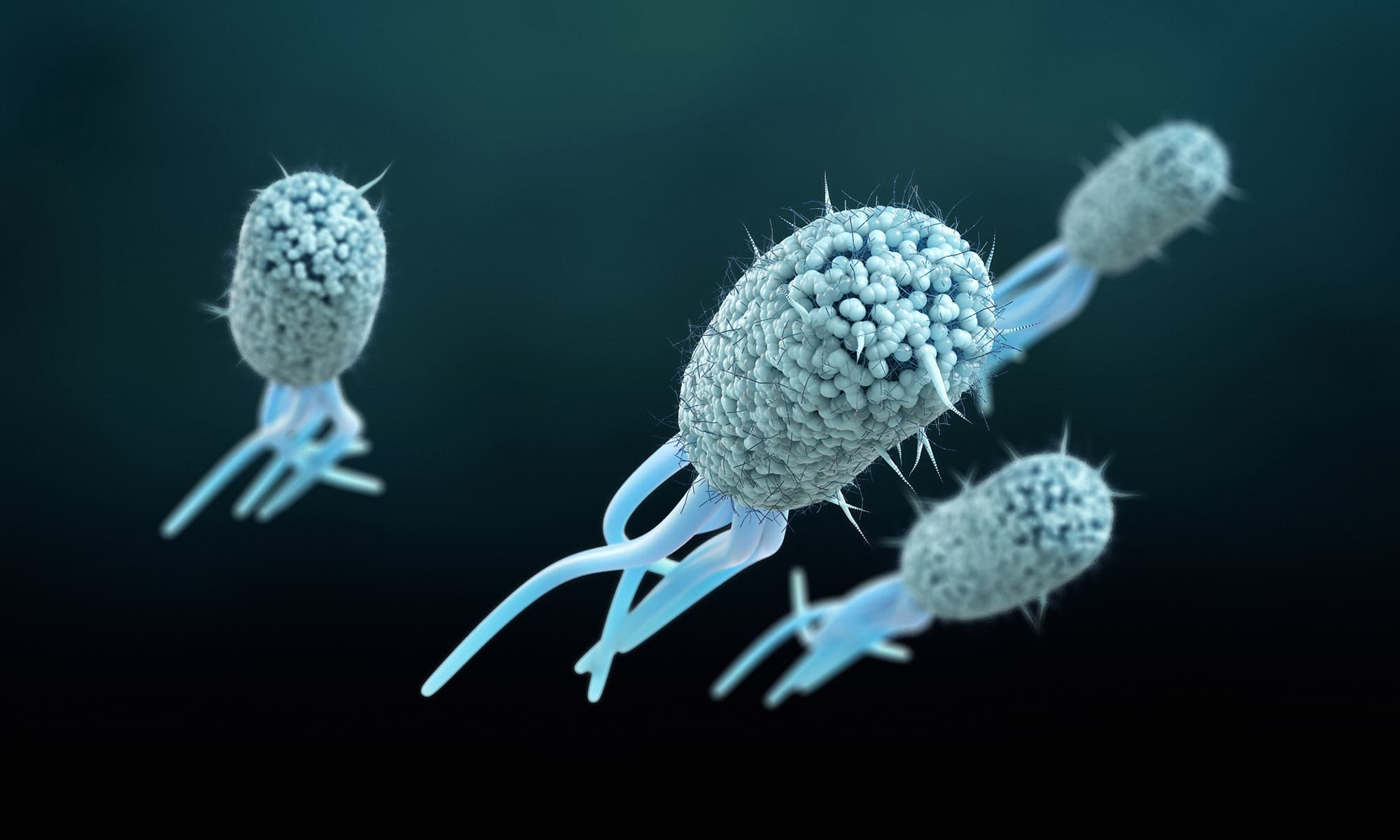

RMIT's NanoBiosensing Facility developed artificial enzymes called 'NanoZymes' which use visible light to create highly reactive oxygen species that rapidly break down and kill bacteria.

Made from tiny nanorods—1,000 times smaller than the thickness of a human hair—NanoZymes combine light with moisture to cause a biochemical reaction that breaks down pathogens.

By simply illuminating the macromolecular catalyst, researchers found that the activity of their NanoZymes increased 20 fold, “forming holes in bacterial cells and killing them efficiently.”

The research dedicated to nanozymes opens a wide range of possibilities for use in antibacterial applications, such as the spread of infections in hospitals and public environments which could be a viable solution to the rising threat of antimicrobial resistance. This use could also be extended to develop self-cleaning, bacteria-free surfaces in everyday products and materials such as paint.