Can skills gaps be solved by learning alone?

Article originally published: https://medium.com/rmit-forward/can-skills-gaps-be-solved-by-learning-alone-d62e72c6441f

Authors: Sally McNamara, development partner at FORWARD — The RMIT Centre for Future Skills and Workforce Transformation — writing with director Peter Thomas and development partners Pete Cohen, Inder Singh, Kate Spencer, Daniel Bluzer-Fry and Courtney Guilliart on addressing the skills gap crisis more holistically through the lens of change management.

In organisational change management, it’s generally accepted that a systems view is required in order to embed effective change— to understand and account for the interconnectedness and impact of one area of the business upon another. We know it’s not enough to introduce a new technology promising greater efficiency, without also re-aligning incentives that inadvertently reward inefficiency. Consider the case of lawyers who have been traditionally rewarded on the number of hours billed. Now there’s machine learning technology that can save many hours of time reviewing documents. Sounds great right? But, it depends. What if your bonus remains tied to hours billed? How eager would you be to change if it meant losing money?

But when it comes to learning, we seem to be stuck in a paradigm of treating it as a discrete ‘learning and development’ (L&D) challenge, rather than taking a systems view. If we are to activate effective adult learning, surely it’s going to take more than buying a company-wide subscription to an online learning platforms.

To address the complexity of the skills challenge at hand, we’d do well to draw upon principles that have been deeply embedded in First Nations knowledge for tens of thousands of years, long before modern business models came into being and bring a deep understanding of how parts of an ecosystem or set of knowledges relate to one another and are continuously shaped by these interrelationships.

“When we consider knowledge systems from a First Nations perspective, we are looking at many interconnected relationships or pieces of knowledge that overlap and interact with each other without conflict. This is often referred to as kinship or balance.”

— Bundjalung, Thunghutti and Muagal man Leeton Lee (Southeast Queensland Regional Coordinator of Firesticks Alliance Indigenous Corporation).

Taking a systems worldview allows us to appreciate the interconnectedness of all things including how incentives must be aligned to desired outcomes. If learning is rewarded mainly through the award of continuous professional education (CPE) credits that bear no timely relevance to a job role — as it so often still is — and L&D teams are rewarded on the number of these credits employees achieve, it’s easy to see how we’re missing the mark.

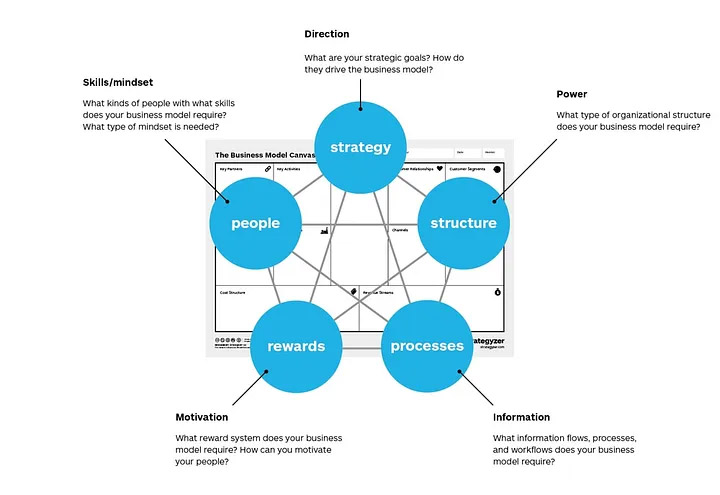

An organisational change model that draws upon systems thinking is the Galbraith Star Model™, which suggests that the following areas require alignment to successfully drive an organisation: Strategy, Structure, Processes, Rewards and People.

A business model can be overlayed with the star, highlighting how the policies and decisions made in one area will have impacts in all of the others. Of course, this is just one model and there are many others, and no model is perfect, but it can remind us to step back and think bigger and consider complex questions such as how are we going to create a culture of lifelong learning to support ongoing and fast-paced upskilling and reskilling?

Star Model™ framework for organisation design (© Jay R. Galbraith)

Star Model™ framework for organisation design (© Jay R. Galbraith)

As we continue to unravel the complexity of the future skills challenge here at RMIT FORWARD, it’s hard to see that the enormity of this ongoing challenge can be solved by L&D teams alone, or even individual learning programs, as diverse and accessible as they may be in delivery.

It’s likely that more significant organisational redesign is required. What if learning became part of the way the whole organisation operated — a driver of organisational structure and strategy — rather than simply an output of L&D alone? And what might be possible if we saw learning through the lens of an ongoing organisational change process, rather than a siloed impossible burden of L&D?

The corporate learning space is estimated to be worth US$360 billion, with the average company spending US$1200–1500 per year per employee, and of course, much more on senior employees.

There’s certainly no shortage of investment in learning products and services, so why are we not seeing the return? In one survey of 1500 managers from 50 organisations, 70% reported they don’t have mastery of the skills needed to do their job today (let alone their next job) and just 12% said they apply learning directly to their job roles.

If access, availability and quantity of learning content is not solving for skills gaps, what will it take?

Microsoft is one organisation that has seen tangible benefit from putting learning at the very heart of its organisational culture and strategy through investing in company-wide change:

For too long we’ve been the know-it-all company, and we need to become the learn-it-all company.

— Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella

Satya goes on to say that part of the power of this “learn it all” concept is that it’s not a one-off program or change intervention:

Saying, Okay, let’s go from know-it-all’s to learn-it-all’s, is to frame it as a continuous process of renewal, [rather than] a transformation from one set of attributes frozen in time to another. This learning culture means that you have to learn every day.

Microsoft’s share price and product development in the last few years of transitioning to a “learn-it-all” culture suggests that it’s paying off. After a decade of flat growth, the share price hit an all-time high in 2018. Taking their cue from Carol Dweck’s “growth mindset” work, they took the need for learning seriously enough to anchor their culture change around it, centered on the belief “that everyone can grow and develop; potential is nurtured, not predetermined, and anyone can change their mindset”.

In this way, learning becomes the very heart of culture and strategy — and necessary to achieve profit growth, rather than a nice to have bolt on.

It’s a huge investment of time, energy, resources — much harder than buying a company subscription to an online learning platform — but is it one that we can afford not to make?

Contact the Workforce Development team to learn more about our services and partnership opportunities.

Acknowledgement of Country

RMIT University acknowledges the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nation on whose unceded lands we conduct the business of the University. RMIT University respectfully acknowledges their Ancestors and Elders, past and present. RMIT also acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and their Ancestors of the lands and waters across Australia where we conduct our business - Artwork 'Luwaytini' by Mark Cleaver, Palawa.

Acknowledgement of Country

RMIT University acknowledges the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nation on whose unceded lands we conduct the business of the University. RMIT University respectfully acknowledges their Ancestors and Elders, past and present. RMIT also acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and their Ancestors of the lands and waters across Australia where we conduct our business.